(PCC) Program on Chinese Cities – Thoughts on Overseas Travels Series

Authors: Ronghui Tan,

lecturer at the School of Public Administration, College of Management and Economics, Tianjin University, and visiting scholar at UNC, with research interests in land cover/land use change (LUCC) monitoring and simulation, and urban growth boundary (UGB). Email: rhtan@tju.edu.cn

As one of the world’s countries that most cherish freedom and democracy, the United States usually places citizens’ rights in a very important position in matters concerning national and people’s livelihood, and this is especially true in urban planning. Since the early 20th century, the United States has had cases of public participation in housing planning, and by the late 1960s, public participation gradually spread throughout the United States, with the role of planners gradually shifting from being government spokespeople to multi-interest coordinators. Theoretically, the theory of public participation in urban planning has gone through stages such as “Advocacy Planning,” “Ladder of Citizen Participation,” “Communicative Planning,” and “Collaborative Planning.” Behind different theories, there is active thinking by the academic community about the representativeness of planning interests, the criteria for the success of public participation, and methods of public involvement. On the practical level, from small towns, and cities to metropolitan areas of different scales, there are many successful cases such as the Denton Plan 2030, Philadelphia City Planning, and Chicago 2020 Metropolitan Planning. The combination of theory and practical experience has made the U.S. public participation system in urban planning increasingly robust and complete. So, what are the successful experiences of public participation in urban planning in the United States that are worth our reference?

First, a well-developed legal system is a prerequisite for public participation in urban planning in the United States. Encouraging public participation in urban planning reflects the government’s intention to protect citizens’ rights to information and equality. In the United States, from the federal to the state level, there are laws to guarantee the public’s right to information and participation in the process of urban planning formulation and implementation. Laws such as the Federal Highway Act and the Federal Transportation Act explicitly stipulate that public participation is a legal prerequisite for urban planning. During the formulation and implementation of urban planning, institutions such as community planning councils, citizens’ advisory committees, and citizens’ planning committees ensure that citizens have legal channels for opinion expression, information feedback, and law enforcement supervision.

Second, the diversification of public participation also provides a certain guarantee for the perfection of urban planning. At various stages of urban planning preparation, decision-making to implementation, citizens can understand relevant planning information and feedback on their value orientation towards the plan, suggest specific planning projects, and vote on specific proposals through public hearings, public advisory committees, stakeholder meetings, teleconferences, information association meetings, public expansion meetings, community forums, promotional exhibitions, websites, and social media. Additionally, government agencies also place great emphasis on “marketing” the value of public participation, using various forms to promote citizen participation in urban planning affairs, such as surveys, television, the internet, magazines, newspapers, letters, and other media, and simulation games. Citizens can feed back their opinions on planning to planners through questionnaires in public places such as coffee shops, supermarkets, and post offices, or construct their ideal future city layout on models through planning games set by the committee.

Furthermore, government planning departments will guide public participation in urban planning in various ways to increase public awareness of participating in urban planning and provide training for this purpose. The training content includes explanations of planning schemes and the imparting of professional skills, such as cognitive mapping training (allowing participants to describe a specific space through drawing and identifying important spatial nodes, characteristics, and relationships with the surrounding environment).

During my visit to the United States, I recently attended a public participation course in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC-Chapel Hill, where I simulated a citizen’s hearing during the preliminary research stage of urban planning for Ontario in the Greater Los Angeles area, and personally experienced the charm of public participation in urban planning.

Usually, during the preliminary stage of urban planning, planners and government department personnel will hold a public hearing similar to a debate through the neighborhood planning committee or public participation advisory committee. The neighborhood planning committee consists of citizens whose main task is to suggest modifications to neighborhood planning projects, and the public participation advisory committee, established under the planning committee, mainly reflects the opinions of community residents. The hearing is composed of arbitrators and citizens, with the main responsibility of the arbitrators being to convene the meeting and coordinate the interests of all parties. The meeting is usually divided into three stages: statement, debate, and summary.

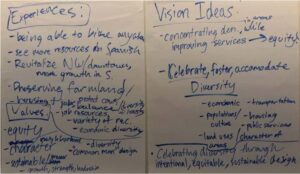

At the beginning of the meeting, the arbitrator will usually inform the citizens about the content and outline of the public meeting, such as “What experiences have you had in this city?” “What do you think the mainstream value orientation of future urban planning is?” “What should the vision ideas for the future development of this city be?” etc. In the meeting statement phase, each citizen representative presents their own ideas about various aspects of urban planning based on personal experiences. Citizen representatives come from different professions, ages, genders, and regions, and the broad representation of delegates ensures to some extent the comprehensiveness and equality of opinions. Usually, issues of concern to all sectors of society are mentioned by most citizen representatives, such as the desire for convenient transportation, high-quality medical and educational facilities, a safe urban environment, abundant employment opportunities, and a well-protected natural ecological mechanism. Of course, due to differences in personal life experiences, environments, and value orientations, controversies are inevitable, such as immigrant representatives paying more attention to welfare and fairness, environmental enthusiasts believing that the focus of planning should be on developing green and environmentally friendly buildings, while developers and some citizen representatives think that expensive green buildings will increase the development burden and put pressure on local finances.

In the debate stage of the meeting, this dispute reaches a climax, and those with different opinions refute each other’s views (Figure 2a). In such cases, the arbitrator usually explains and coordinates the doubts of some representatives based on the opinions of the majority to reach a consensus (Figure 2b).

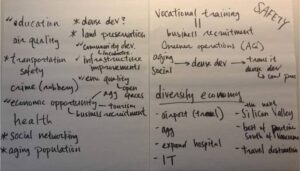

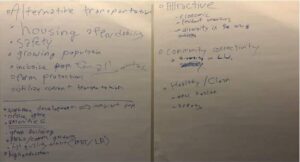

In the summary stage of the meeting, the arbitrator will read the consensus reached by the public at this debate and arrange these consensuses in order of priority and task urgency, and will also inform the public of the reasons for each decision-making (Figures 3 and 4).

In this case, citizen representatives ultimately believe that urban planning needs to focus on the following aspects:

(1) The diversity and convenience of transportation methods;

(2) Resource and environmental protection and sustainable urban development;

(3) The connectivity of social networks and neighborhoods;

(4) Employment and social equity (between different races, and different income groups);

(5) Urban safety, including reducing crime rates, improving air quality, protecting public health, etc.

The American urban planning public participation mechanism guarantees citizens’ right to information and participation, and increases the transparency of planning, making the planning no longer just a formal paper representation of “drawing on paper and hanging on the wall”, but a real “bottom-up” public participation in the future city layout display. Secondly, the public participation model has changed the traditional planning concepts of planners and various stakeholders, promoted the transformation of government functions, and cultivated citizens’ sense of social responsibility. For China, the public participation model of American urban planning in legislation, organizational implementation, and education and training is worth our deep reflection and reference. However, I also have some doubts. First, when the public participates in urban planning on a large scale, if the opinions of different interest groups differ or are completely opposite, how do planners, planning committees, and local governments coordinate? Secondly, given the wide range of the public with diverse backgrounds, and most citizens are not professionals in urban planning, their value judgments are mostly based on personal interests, so how to ensure that public opinions and schemes conform to the optimal urban planning scheme that combines social, economic, and ecological environment benefits and sustainable development?