(PCC) Program on Chinese Cities – Thoughts on Overseas Travels Series

Authors: Mingyu Zhang,

PhD student in Architectural Engineering at Zhejiang University, jointly trained PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Email: mingyuzhang0313@gmail.com

In February 2017, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development held a pilot work meeting on urban design, recognizing the important role of urban design in controlling urban form and proposing to clarify the status and requirements of urban design in the planning system. In the United States, Form-Based Codes (FBC) have emerged as a new tool for controlling urban form, already in use in over 70 cities. Initially encountering FBC in class, one might think it an acronym for an organization similar to the FBI, sparking a certain curiosity. However, peeling back its seemingly mysterious veil, FBC’s rich content indeed warrants study and reference domestically.

FBC, standing for Form-Based Code, promotes the formation of urban forms within a planning scope by establishing clear material form design elements and regulations. Its rise is influenced by the New Urbanism movement, as traditional zoning was found inadequate in enhancing land use mix and ensuring orderly plot form design. Thus, city governments and planning experts started exploring a new legal planning tool in the 1990s, hoping to control urban sprawl while enhancing the plot function mix. As a result, the new growth management tool, FBC, was born, focusing more on micro-level land use management and zoning through a variety of design parameters.

Generally, FBC includes a Regulating Plan, Definitions, Public Standards, Building Standards, and Administration, with possible additions of Landscaping Standards, Signage Standards, etc., depending on the planning object’s actual situation. From a content organization framework perspective, FBC has much in common with urban design ordinances, yet the differences are clear. First, FBC is a mandatory regulation passed by local legislative bodies, not a guiding measure like urban design guidelines. Second, in terms of content, FBC’s design requirements are more detailed and profound, adding aspects like building floors, functional mix, and landscape design, providing very detailed design standards for certain types of plots.

Currently, FBCs in use across the United States can be broadly categorized into three types: Mandatory, Optional or Parallel, and Hybrid. The difference between the first two lies in that, once passed by the council, the mandatory form control standards completely replace the plot’s original planning and design guidelines; while the optional FBC gives developers the choice to follow the original plot design guidelines or adopt the new FBC standards. Clearly, mandatory standards ensure a more orderly and coordinated form design, avoiding contradictions when two systems are applied. However, due to the U.S. political system, implementing a mandatory standard often requires city governments to invest significant manpower, funding, and time to balance the interests after completely replacing the original rules. This is a major reason some city governments prefer the optional standard. The Hybrid standard is a balance between the two, integrating traditional zoning guidelines with FBC content, thus promoting the standards’ implementation through a variety of incentive clauses outside of FBC’s original content.

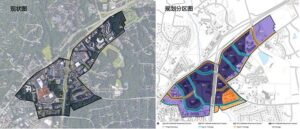

Lastly, take the Ephesus/Fordham Form District in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where the author is located, as an example. This FBC is a hybrid standard, mainly including land zoning, land use management, and design standards. The standard is based on the principle of walkability, divided into Walkable Residential and Walkable Mixed Use categories, further subdivided into four subcategories. For each subcategory of plot, a detailed land use nature category table is provided, listing different land use natures within different plots as permitted (P=Use Permit), permitted under special conditions (S=Use permitted following Town Council approval of Special Use Permit), or not permitted. In design standards, detailed parameters are drafted for plot building height, facade design, street settings, as well as landscape design, signage systems, lighting systems, and parking configurations, allowing developers more freedom on a coordinated basis.

Comparatively, although the importance of form control is increasingly recognized by some city governments domestically, a large number of urban designs still stop at a few cool renderings and lengthy advisory ordinances, lacking a real implementation system. Based on this, some cities have begun exploring the combination of urban design and detailed control planning to incorporate form control into the legal planning framework, which has great similarities with the hybrid FBC integrating zoning and form design guidelines. Therefore, FBC’s content framework and management implementation system can provide references for domestic regulations, aiding in the reform of urban design work.