(PCC) Program on Chinese Cities – Thoughts on Overseas Travels Series

Authors: Li jia,

Associate Professor at the School of Economics and Management, South China Agricultural University; Visiting Scholar at UNC; Research Focus on Land Use Planning and Land Policy. Email: scaujl@gmail.com

Having just arrived in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, the first thing that struck me was the lush greenery. The abundant green soothes the eyes and the fresh air is invigorating (Image 1). Opening Google Maps, I noticed that the town is dotted with parks. While enjoying this beautiful environment, I couldn’t help but contemplate the American urban park system and its provisioning mechanisms.

This semester, I chose to take the course “Development Impact Assessment” which mainly involves the evaluation of public facilities, and this provided me an opportunity to learn about the historical development of parks in the United States.

I. Four Developmental Stages of American Urban Parks

- 1850—1900: The Natural Park Era

Due to rapid industrial transformation at the end of the 19th century, many cities became unhealthy places to live, necessitating a space to restore the natural, healthy aspect of urban life. Thus, urban parks were born. Most city parks were established between 1850 and 1900, including famous ones like Central Park in New York and Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park, is known as “the father of American landscape architecture.” He believed that parks and open spaces were crucial for the psychological health of urban residents. The park designs of this era were rustic, carrying a strong local flavor. Officially, parks served all social classes, but they primarily catered to the middle and upper classes with concerts, designs, and sculptures that reflected the tastes of the affluent, whereas popular activities like animal acrobatics and ice skating were scarcely found. A day’s wage for a working-class individual was equivalent to the cost of transportation to these parks, which also commonly featured racial segregation. This period also saw the emergence of national parks. - 1900—1930: The Reform Park Era

If the “Natural Park” represented elite status and Emersonian ideals—Emerson being a seminal figure in American intellectual history who believed in humanity’s inherent ability to experience and beautify nature—the early 20th century “Reform Parks” reflected societal change. Social reformers like Jacob Riis and Lincoln Steffans worked to improve the living conditions in urban slums in terms of housing, food, and water quality, while also shifting the focus of the park movement toward small, community parks. This era saw an increase in plantings and facilities like tracks, swimming pools, playgrounds, indoor gyms, and lockers, providing a place for social interactions and activities, reshaping American social culture; parks attracted a large number of immigrants and became a means for politicians to garner support. - 1930—1950: The Recreational Facilities Era

In 1930, Robert Moses became a park commissioner, marking the end of using parks as tools for social reform. Due to the Great Depression and tight government budgets, rational urban planning emerged, focusing on improving entertainment standards and efficiency in park construction. During World War II, parks were used for civil defense. It was not until the 1950s that they were opened to the public. The construction of parks now focused on meeting recreational needs, providing economical and practical indoor and outdoor activities for residents of all ages. Suburbanization made this period’s urban parks almost exclusively domains of the poor. - Post-1960s: Parks and Cultural Change

The inner-city riots of the 1960s shocked the public, painting inner-city and urban parks as high-crime and unsafe areas. The anti-war movement, “Flower Children,” and the Baby Boomer generation altered the dominant American culture. Park officials adopted various proactive measures to encourage middle-class return to the parks, ensuring a safe experience for inner-city residents. Design and facility trends from New York’s park commission during this period spread to other areas, incorporating cultural activities like rock music, jazz festivals, wine tasting, and kite flying. Sports facilities were also upgraded, and skate parks began to emerge. - Private Parks, Tourist Cities, and Broader Roles

As family incomes and leisure time increased, the private sector became more active in providing recreational activities and services. Theme parks, convention centers, baseball and soccer stadiums flourished. Meanwhile, the tourism industry rapidly emerged as one of the most dynamic economic sectors in the world. Parks, as elements of “destination cities” and integral parts of urban areas, attracted emerging economic industries; “eco-parks” and “eco-tourism” also began to rise. Thus, park design and community construction, open spaces, and green communities integrated to maintain public health and reduce urban heat island effects. Urban renewal projects in old city districts saw the use of unmanaged open spaces as a vital part of community rebuilding, with nonprofits in cities like Boston and Philadelphia transforming vacant lots into play areas and community gardens.

II. Operational Management of American Urban Parks

As we stroll in the beautiful surroundings of community parks, enjoying various conveniences at low prices, we might wonder where the daily costs of these parks come from. For instance, many children in our neighborhood learn tennis in the community park, where an introductory course costs only $45 for 8 sessions, cheaper than similar courses domestically. In fact, the planning, construction, and financing of parks are typically responsibilities of the city or county, and many cities have their own elected park district boards. In the early 20th century, park commissions were independent of municipal government. During World War II, they became part of the government system, with park functions becoming essential municipal services. Park commissions could apply for federal and state funds.

We live in Sunstone, a 5-minute walk to the community park, and a 30-minute walk to Battle park, with Falls Lake, Carolina North Forest, and Jordan Lake all within a 30-minute drive. These places have become our regular weekend destinations. From the small town of Chapel Hill, it is clear that there is a hierarchical system of parks based on accessibility, size, facilities, and capacity.

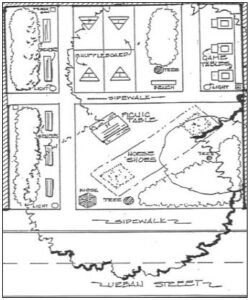

1. Mini-Parks

Serve a radius of about 400m, less than 0.4 hectares in size, with few recreational facilities like swings and sand areas, catering to densely populated residential areas (Image 2).

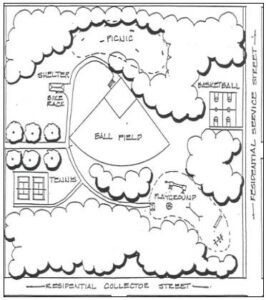

2. Neighborhood Parks

Serve a radius of 400-800m, approximately 2-8 hectares in size, accessible on foot and also providing parking lots to serve people from further distances (Image 3).

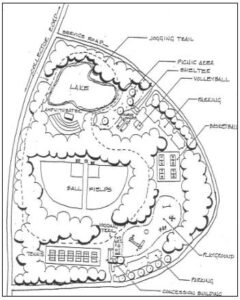

3. Community Parks

Serve a radius of 1.6-8 km, over 8 hectares in size, approximately serving 20,000 people, offering a variety of facilities such as tennis courts, swimming pools, gyms, meeting rooms, parking lots, and lights for nighttime use (Image 4).

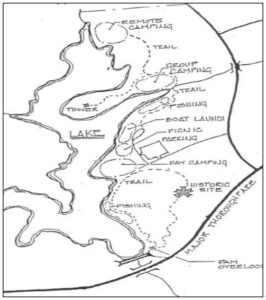

4. Regional Parks

Serve a half-hour drive radius, typically around 32 km, at least 30 hectares in size, capable of serving over 40,000 people. In addition to the above facilities, these parks also offer camping, hiking, gymnasiums, museums, and other places and services (Image 5).

The functions and forms of urban parks are increasingly diverse, including specialized sports facilities like ski resorts, professional swimming centers, equestrian centers, skateboard centers, botanical gardens, greenways, and other botanical cultivation bases and outdoor recreation areas. In the United States, there is also the concept of “Dog Parks.” Professor Bendor mentioned that UNC campus also has such a dog park, although I have not yet located it since I do not own a dog.

III. Characteristics of American Urban Parks

While touring various American cities, I visited many urban parks and was deeply impressed.

1. Emphasis on Natural Wilderness

Whether it’s the renowned Central Park in New York (Image 6) or a lesser-known community park in a small town, all exhibit a strong American pastoral style, likely influenced by “the father of American landscape design,” Olmsted. His hallmark, Central Park, is initially captivating due to its natural wilderness—with tens of hectares of dense forests, open lawns, large bodies of water, and naturally preserved rocky landscapes, devoid of deliberate man-made decorations. Stepping from the luxurious Fifth Avenue’s bustling offices into Central Park feels like traveling through time, instantly eliminating worldly thoughts, satisfying the desire to have nature within an urban setting, making it a modern urban park archetype. In Chapel Hill’s numerous parks, large forests and winding paths are filled with “wilderness.”

2. Publicness

The most significant characteristic of American urban parks is their publicness—they are open to the public for free, just like streets and plazas, forming part of the urban public space. Parks improve the physical and mental health of citizens, contributing to the healthy operation and development of cities.

New York’s Paley Park, though small, is incredibly appealing (Image 7). The park is street-facing, allowing people easy access from the busy urban areas to this charming and pleasant little haven. Rhode Island’s Providence Riverwalk & Water Place Park is a popular venue, known for its perennial public cultural and artistic events. Visitors and residents can enter at any time to watch or participate. Within Chapel Hill’s community parks, it’s common to see playful children, leisurely walkers, carefree cyclists, and tireless joggers enjoying the fresh air.

3. Rich Activity Programs

Most city parks ensure the daily free use of venues while also organizing a variety of activity programs. Chapel Hill’s parks offer activities ranging from social gatherings for the elderly, interest training, sports and fitness for adults, parent-child activities, meeting room rentals, to basketball, tennis, bowling, climbing, day/night care, and summer/winter camps for children. These activities are closely aligned with the actual needs of surrounding residents, and their effectiveness is evaluated annually. The fees for these activities are in line with the overall income levels of the community residents. These measures not only provide convenience for residents and strengthen community cohesion but also generate some income for the maintenance and operational management of the parks.

Domestically, the importance of open space construction is also increasingly recognized. In Guangzhou’s densely packed Zhujiang New Town, small gardens, riverside parks, and museums abound, and greenways stretch across the city. As dusk falls, parks and plazas become lively with dance. Meanwhile, across the ocean, parks are filled with runners and playful children. Globalization and the internet have long made the world a small village.