(PCC) Program on Chinese Cities – Thoughts on Overseas Travels Series

Authors: Lei Xia,

Doctoral candidate in urban and rural planning jointly trained by Harbin Institute of Technology and UNC, specializing in green planning for cold regions and the character planning of villages and towns in cold areas. Email: xrayhit@hotmail.com

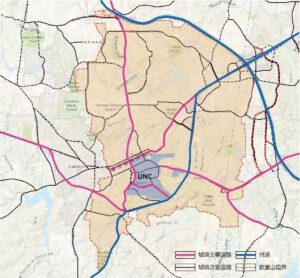

The street is the carrier of urban activities; a lively street signifies a vibrant city[1]. Franklin Street, named after Benjamin Franklin, is the famed main street of Chapel Hill, North Carolina. With the establishment of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill along its southern side in the 1690s, the street gained prominence. Initially, Franklin Street housed only residences, a few shops, churches, and a post office; later, Sutton’s Drug Store opened in 1923, offering medicines and food to the community. In 1949, the Morehead Planetarium was built on East Franklin Street, becoming the first astronaut training facility for NASA. Over time, Franklin Street developed from a mere dirt road into a major hub for tourism, entertainment, dining, shopping, and social gatherings. Today, Franklin Street extends east through a commercial area and the campus, connecting to the historic residential areas of Chapel Hill and west to the town of Carrboro (Image 1), with restaurants, bars, coffee shops, and bookstores lining the street (Image 2). This street is also renowned for its vibrant cultural atmosphere, lively nightlife, and festive activities. On April 4th, when the University of North Carolina men’s basketball team won the NCAA championship, students and fans from gyms, dorms, and bars flooded Franklin Street, lighting bonfires to celebrate (Image 3).

The vitality of a street springs from its diverse spaces and social interactions. Jane Jacobs believed that urban streets should meet several conditions to be diverse: they must serve more than one primary function, preferably at least two; they must be short and easy to navigate; buildings should be varied in age and condition; and there must be a high density of people[1]. The diversity of street functions allows for activities such as shopping, leisure, socializing, working, and solitude. As the university expanded, the number of shops along the street increased, reducing the public spaces available for residents and students and making pedestrian areas feel cramped (Image 4). Meanwhile, traffic accidents on Franklin Street, often involving motor vehicles and pedestrians or cyclists, have raised significant concerns about traffic and pedestrian safety. Thus, improving pedestrian spaces, enhancing street facilities, beautifying street landscapes, and ensuring traffic safety have become focal points in the redesign of Franklin Street. In 1993, Chapel Hill’s comprehensive street plan began to enhance the pedestrian environment on Franklin Street, adding retail stores, dining venues, and public leisure spaces, laying the foundation for diverse street development. Over more than twenty years of planning, the street environment has been enhanced and street facilities have been improved. The street redesign incorporates existing spatial resources and extensively gathers local residents’ opinions, focusing on the following aspects:

1. Intensive Use of Road Resources, Optimization of Pedestrian Spaces

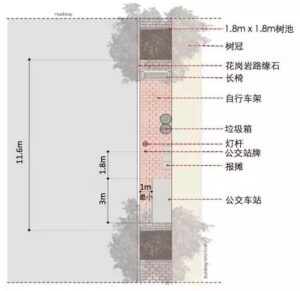

Improving pedestrian spaces and encouraging walking are vital for maintaining the vitality of Chapel Hill. The design includes upgrading the pavement of walkways, strategically placing greenery and street furniture to provide a comfortable walking environment (Image 5). Pavement materials such as colored concrete and stone are used to visually integrate street buildings, landscapes, and facilities into a coherent space. The pavement color coordinates with building colors to provide a stable visual background (Image 6). Additionally, changes in pavement create a sense of depth in street spaces and delineate different functional areas. Crosswalks use red brick paving, contrasting with the gray asphalt to serve as a visual cue (Image 7); tree pits and flower beds between pedestrian paths and roadways beautify the environment and separate pedestrians from vehicles, creating a comfortable and safe walking space (Image 8); street trees also provide shade and shelter for pedestrians. Comfortable walking distances are considered to be 400-500m, and benches are placed near pedestrian paths, open spaces, and bus stops to provide resting spots for pedestrians and waiting passengers (Image 9). The expansion of pedestrian spaces and environmental improvements also create spaces for economic interactions. Franklin Street, filled with shops and with a diverse street-front interface, becomes Chapel Hill’s most popular spot when the weather is good, as people dine and chat outdoors.

2. Rationalizing Public Space Resources, Adding Pocket Green-spaces

The existing public spaces and landscape resources on the street are analyzed in conjunction with crowd hotspots and active commercial areas to efficiently use and unearth public resources, enhancing street space utilization. Different scales of open space nodes are added along the street to form a street landscape system. Pocket greenspaces are created using setbacks between buildings or gaps between them (Image 10), offering unexpected delights to passersby who discover them during their walks. Such diverse open spaces increase spontaneous street activities, playing a crucial role in contributing to the vitality of the street and the small town. Spontaneous activities, influenced by external spaces and voluntarily initiated by people, bring the most joy[5].

3. Introducing Public Art Designs, Enriching Street Visual Features

Public art represents local culture, and artistically treating street space details can enhance the street’s interest and reduce fatigue for walkers. The integration of public art with street scenes brings novelty to pedestrians and increases the small town’s attractiveness. In the Franklin Street update, public artworks are displayed either as standalone installations in open spaces or integrated with street surfaces and building facades (Image 11). The integration of art with street furniture (like information kiosks and lamp posts) can embellish the street, enhancing its visual identity (Image 12).

4. Incorporating Local Customs, Hosting Festival Activities

Local festivals often leave lasting impressions, with the annual Halloween event on Franklin Street being particularly famous, drawing thousands of residents of all ages from the town. Additionally, street fairs held on Franklin Street attract tourists and provide opportunities for the town to showcase itself. To better serve these events and meet diverse needs, the Franklin Street redesign also includes additional public parking and improved barrier-free facilities to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

On Franklin Street, which has seen over a century of urban life, the vibrant street continues to bring endless vitality to Chapel Hill.

Note: Images not sourced are taken by the author.

References

[1] Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities[M]. New York: Random House, 1961. [2] Town of Chapel Hill. Streetscape[EB/OL]. (2009-06-15)[2017-04-21]. http://www.townofchapelhill.org/town-hall/departments-services/business-management/capital-improvements-program/streetscape. [3] CBS North Carolina. Pandemonium on Franklin Street as Tar Heels win national championship[EB/OL]. (2012-01-13)[2017-07-17]. http://wncn.com/2017/04/03/franklin-street-packed-in-chapel-hill-as-tar-heel-fans-celebrate-championship. [4] Daily Tar Heel. Multimedia[EB/OL]. (2017-04-03)[2017-04-21].http://www.dailytarheel.com/multimedia/9061

[5] Gehl J, Koch J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space[M]. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987.